As the tech industry has grown and software has begun to “eat the world”, a new knowledge economy has taken shape that values intellectual property (trademarks, patents, and ideas) more highly than old-school equipment in factories.

As knowledge businesses have grown, so too has the value of their intellectual property (IP). Companies now routinely buy, sell, trade, and litigate over patents and stuff so seemingly minute that the average person struggles to understand how the ability to pinch two fingers together on a mobile phone could be patentable in the first place.

International companies are well-known for using offshore holding companies to house much of this intellectual property. This, in turn, leads solo entrepreneurs to ask themselves if they need a similar structure as well.

There are certainly many benefits to having a proper tax structure for every aspect of your business, including IP.

However, there is a very significant difference between the tax planning of a massive international company and a one-man-show consulting business or small-scale company.

Nevertheless, this difference does not mean you cannot or should not offshore your business’s IP assets; it simply means you will need a different strategy that fits your business.

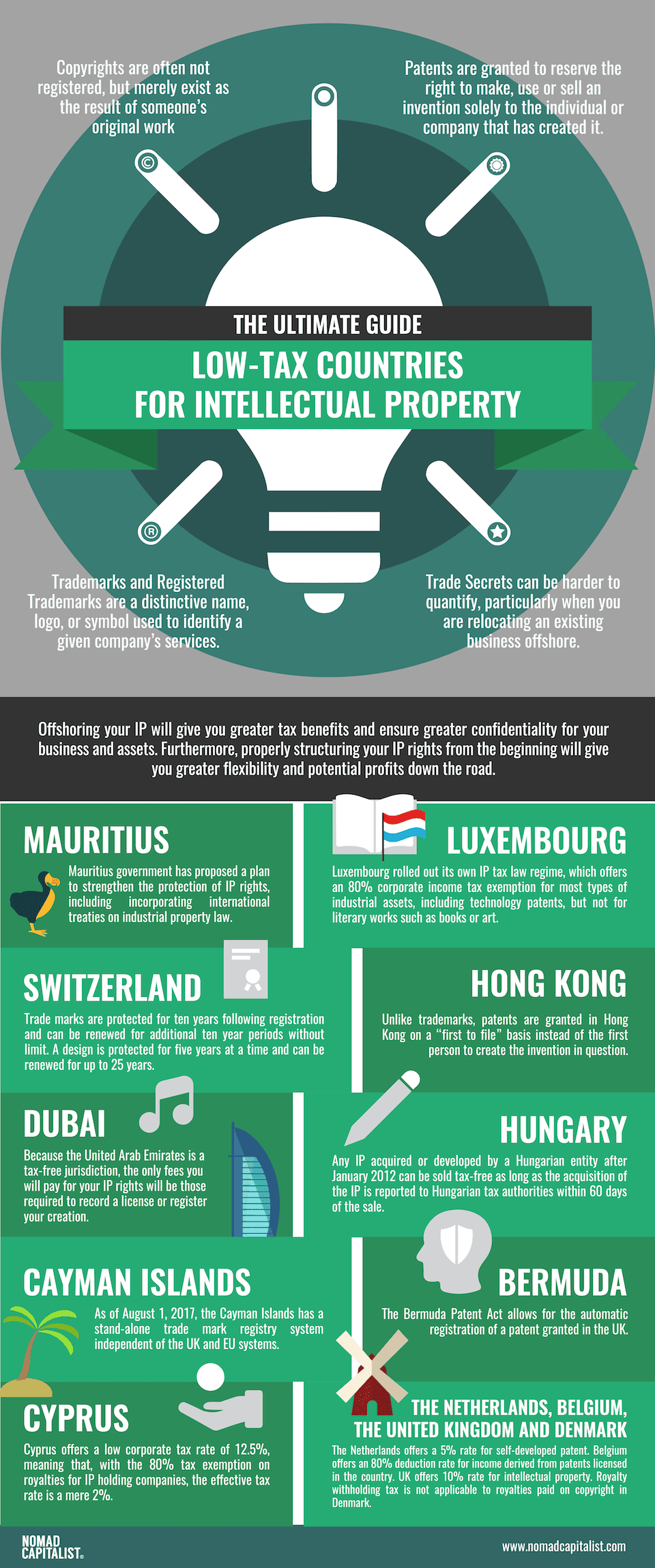

Offshoring your IP will give you greater tax benefits and ensure greater confidentiality for your business and assets. Furthermore, properly structuring your IP rights from the beginning will give you greater flexibility and potential profits down the road.

However, before delving into the finer details of how to structure your company’s IP offshore, let’s take a closer look at intellectual property on its own.

Intellectual property is not tangible. Rather, IP is composed of the intangible ideas, creations, and concepts developed by individuals and companies. Such concepts are usually discussed in the media when referring to Apple suing Samsung over some mobile technology, but if you have a business then it’s quite possible you have some IP of your own. Of course, some IP is more valuable than others.

While intellectual property can be trademarked, patented, or copyrighted for use by its developer, it is often licensed out to third parties in exchange for royalties. Anyone who has ever watched Shark Tank has heard investor Kevin O’Leary shouting at entrepreneurs to collect a royalty payment by licensing their patent rather than manufacturing their own patented product.

Various types of IP include:

Copyrights are applied to the creation of an artistic work and are granted to individuals such as book authors, songwriters, or even software coders. The contents of this website, and likely yours too, are copyrighted. Copyrights are often not registered, but merely exist as the result of someone’s original work. That said, it may be prudent to register your work — anything from a book to software — with the appropriate authorities.

Patents are granted to reserve the right to make, use or sell an invention solely to the individual or company that has created it. Usually, patents do not last forever, with a notable example being on pharmaceuticals. Unlike copyrights, patents are carefully scrutinized by a government body to ensure that they are legitimately new inventions. Patents are also more likely to be the subject of litigation.

Patents may be registered on a national level; for example, in the United States they are registered with the USPTO. They can also be registered on a regional level, which is the case in Europe where they can be registered through the European Patent Office. While famous inventions such as the telephone received patents, most patents are hard for anyone outside of the immediate industry to understand.

Trademarks are a distinctive name, logo, or symbol used to identify a given company’s services. “Nomad Capitalist” is a registered trademark indicating what we do and protecting use of our mark. Like copyrights, there is some inherent trademark protection merely by using a mark in commerce, although it is typically better to register the trademark to increase protection against infringement.

As with patents, trademarks may be registered in a single country or at a regional level such as at the European Trademark Office. Large multi-national companies like Coca-Cola will typically trademark their name and logo in every country they do business in, even though trademark protections are stronger in some countries than others.

There are other types of intellectual property, such as design works and trade secrets. These can be harder to quantify, particularly when you are relocating an existing business offshore.

For the right type of business, proper structuring of IP ownership combined with proper routing of license payments can lead to substantial tax savings. Generally, intellectual property moved offshore is structured in one of two ways.

The first and easiest way is for IP to simply move offshore with the rest of the company. This can make sense if you are the one using your own intellectual property and plan for it to appreciate in coming years.

For example, if your Australian e-commerce company is paying a high tax rate, you may want to move the entire business overseas in order to lower your total tax rate. In this case, your consideration goes beyond merely the trademarks and copyrights and into the best place to structure an offshore company.

One consideration when moving your company offshore is the value of any intellectual property it owns. Generally speaking, you can’t simply give one company’s property to another company. If you could, you might as well give it to me as far as the taxman is concerned. That means that if your domestic company owns IP, you need it properly valued and then transferred to your new company.

In some countries, such as the United States, there may be certain tax-free reorganization laws that allow you to move your assets from one company to another without tax consequences, but this must be done properly.

The second way to migrate your assets is to establish a separate licensing company that holds the intellectual property. In this case, you may donate or sell existing knowledge assets to a company in a zero- or low-tax jurisdiction that plays nicely with royalty payments.

The offshore company holding the assets then licenses some or all of the rights for the use of the IP directly to an end-user in exchange for royalties, or to an intermediary or agency in a country that offers tax treaty benefits and exemption from tax withholding for passive income such as royalties.

This is where licensing intellectual property becomes difficult because each country involved has its own set of rules for transfer pricing and taxation of royalties. Your country of citizenship (particularly for US citizens), current country of incorporation, new country of the operating company incorporation, new country of the holding company incorporation, and the end-user of the licenses — if any — must all be considered in a legal, low-tax intellectual property structure.

You can see how things can get confusing, especially if you license your assets to third parties who may set terms on when, where, and how you will be paid.

Part of the challenge is that most developed world countries have specific rules about transferring money to low-tax countries for such intangibles as “consulting” or “licensing fees”. Many of these countries apply withholding taxes that make sending the money offshore undesirable. Therein lies the challenge in creating a proper structure.

That is why intermediary companies often exist; a developed world company can license IP to an onshore company under more favorable terms thanks to tax treaties, while that company may in turn then deal with a tax-free or ultra low-tax country. In such an example, a UK company might transfer money to Luxembourg which would keep a taxable spread before transferring the balance to a lower-tax country.

It can all get rather tricky for small companies, which is why the tried-and-true method of offshoring the entire company, including you as the owner, can often make sense.

If you do choose to offshore IP alone, you will want to make sure that all companies play nicely with your existing corporate structure, which likely means tax treaties with low withholding tax rates. It is also beneficial to use countries that can offer “advance rulings” on your structure. By asking the taxman if your structure is compliant before putting it into service, you can pay a little now to save a lot later.

The undeniable trend is that intellectual property ownership is held offshore. My registered trademark is owned by a Hong Kong company, and I had no problems getting that done.

I’m not alone; since the offshore trend began in the 1980s, the number of European trademarks issued to low-tax and tax-free countries has more than quadrupled.

However, the countries applying have started to change as high-tax countries create special tax schemes for intellectual property specifically in an effort to bring in capital. As I often say, onshore is the new offshore, and this is true for IP licensing as well.

This is driven, in part, by an onshore shift spoken of by KPMG: “They must constantly balance opportunities for IP tax benefits in Country A with the risk of highly public anti-tax avoidance campaigns in Country B or C”. Tax agencies around the world want to make sure they don’t leak profits to low-tax countries, which is — again — why I often suggest just moving your business to a low-tax country and removing them from the equation entirely.

One trend as of late is high-tax countries imposing new, unilateral rules to tie where profits are booked to where work is done. It is more difficult than before to form a low-tax company and transfer knowledge assets in a place where you have no office and no staff. The way they see it, you should pay dearly for creating an invention or idea in their country and wanting to sell it to someone else later.

As the world becomes more tax transparent, there is a lot of uncertainty about transfer pricing and offshoring intellectual property assets. The more complicated of a structure you create, the more difficult it will be to not only manage but also remain tax compliant.

Some countries have sought to encourage entire businesses to move to their shores by developing IP-friendly, tax-friendly legislation. Ireland is one of these countries; just visit Dublin and you’ll hear about the housing shortage caused by every tech company under the sun moving in. For large companies, building real operations for R&D in a tax-friendly jurisdiction is just as important as it is for small companies like the ones you and I own.

If you’re Facebook or Apple, moving your trademarks and patents to a low-tax country is probably a great idea. However, it’s important to understand that there is a big difference between a multi-national US company and a small business owned by a US citizen.

Too many times, I’ve heard from US citizens who read some article on the internet about how easy it would be to transfer some asset into an offshore company and save big on taxes. In some cases, these entrepreneurs were convinced they could continue to live in the United States and earn royalties on their IP using an offshore company.

The reality is that US citizens are subject to special tax rules which could make a company specifically designed to hold trademarks and patents bad for taxes. That’s because US citizens are subject to tax on worldwide income, including so-called Subpart F passive income.

If you are a US citizen, it is important to have a well-thought out strategy for moving your business offshore from the beginning. We’ve written about the many mistakes that US citizens make when going offshore on our other blogs, and IP holding companies are just another potential mistake. The last thing you want to do adjust your lifestyle and offshore your business to end up with a tax bill from your Subpart F royalty income.

Before we take a look at the most reputed low-tax countries for holding your knowledge assets, let me ask the question: do you really need a separate company exclusively to hold these assets?

If you’re a large, publicly-traded company doing business on the ground all over the world, the answer might well be “yes”. Then again, if you’re head of Tax Strategy at Google, I would hope you’re consulting the legion of lawyers you already have on staff, and not Googling for “best countries for holding intellectual property”.

The truth is that, while a separate IP holding company may make sense for some small businesses, most of us can merely hold our company’s assets in a single offshore company. In my experience as someone who actually does business with offshore corporations rather than someone who sells them, simple is usually better.

For many entrepreneurs, rather than trying to create a complicated network of companies that exchange money back and forth, the question is simply, “Where do I incorporate my company offshore?” Not only are these large structures usually inefficient and costly to maintain but they involve other risks that are rarely considered, such as the possibility that your bank will find your version of transfer pricing to be suspicious and cause you problems.

As always, my approach is to understand the END RESULT desired by creating an offshore structure, and then to work backward to create the simplest, most affordable structure to achieve that goal. The reality is that while IP companies are valid for some people, many others who are looking to form them have been wrongly convinced they need one by some internet lawyer on a tiny island.

As is usually the case in the offshore world, the “best” is hard to define. Each person and each business has its own circumstances and requirements that make their best country different from someone else’s best country. In some cases, a few tiny details could change an entire strategy.

As such, it’s important to create a thorough Plan before moving your IP offshore.

Located just off the eastern coast of Africa, the island of Mauritius has long offered favorable tax policies for businesses. However, it is not a zero-tax jurisdiction. All corporate income accrued in or derived from a Mauritius company is subject to a 15% corporate income tax rate. The same rate is applied to IP royalties in the form of a withholding tax.

In the past year, the Mauritius government has proposed a plan to strengthen the protection of IP rights, including incorporating international treaties on industrial property law. The new bill will address patents, utility models, the Patent Cooperation Treaty, layout designs, the protection of new varieties of plants, industrial designs, the Hague Agreement, as well as marks, trade names, geographical indications and the Madrid Protocol. This will make IP related issues in Mauritius much more accessible, a good characteristic for solo entrepreneurs looking for an offshore jurisdiction for their IP.

Despite commonly being thought of as an offshore haven, Luxembourg is not a tax haven and actually taxes corporate profits at around 28%. However, Luxembourg has never had any specific withholding tax rules which has allowed it to play the role of intermediary, given its access to tax treaties as part of Europe.

However, in 2007 Luxembourg rolled out its own IP tax law regime, which offers an 80% corporate income tax exemption for most types of industrial assets, including technology patents, but not for literary works such as books or art. For tech companies and others with patents who want a secure jurisdiction, Luxembourg’s low net tax rate of 5.6% is not bad at all.

The challenge is ensuring that money movements meet Luxembourg’s criteria. The requirements have been tightened in recent years due to new anti-money laundering laws. If you’re not averse to the paperwork, Luxembourg could be the jurisdiction for you.

Switzerland offers a wealth of IP rights for everything from patents to trade marks and copyright to design rights. Novel qualifying inventions can be protected in Switzerland for a maximum of 20 years and pharmaceuticals and pesticides can be granted an additional five years after the original 20 year period. Trade marks are protected for ten years following registration and can be renewed for additional ten year periods without limit.

Artistic and literary works as well as computer programs are all protected by copyright law in Switzerland from the date of their creation. Registration is not possible, but neither is it necessary. Design rights — which protect the appearance of two- and three-dimensional products — are also protected under Swiss law. A design is protected for five years at a time and can be renewed for up to 25 years.

As long as IP is sold as part of an individual’s private assets, the gains from such a sale are not taxable. However, if the sale of the IP belongs to an individual’s business or partnership assets, income taxes are due at ordinary rates on all IP-based income. Taxes in Switzerland can be as low as 17% and do not go above 40%, but those rates aren’t low enough to mess around with. If you are going to keep your intellectual property in Switzerland, make sure it is registered as a private asset.

Trademarks intended for or currently in use in Hong Kong can be registered with the jurisdictions Intellectual Property Department (IPD). The system operates on a “first to use” basis, meaning that IP rights to a given trade mark are based on who used it first instead of who was the first to register. However, it is still easier to enforce and commercialize a mark that is registered. Trademarks can be held indefinitely, but must be renewed every ten years.

Unlike trademarks, patents are granted in Hong Kong on a “first to file” basis instead of the first person to create the invention in question. Consequently, it is important for inventors to patent quickly. More importantly, Hong Kong patents can only be registered to patents already obtained in three other jurisdictions: the PRC (China), the European Patent Office, or the UK Patent Office.

The process to obtain a long-term patent good for twenty years can take up to three to five years. Short-term patents do not require as many formalities and investigations and can be granted for a much lower cost and shorter timeline. They are only good for a total of eight years.

Copyright is granted automatically in Hong Kong upon creation, but it is recommended that any authors, artists, or programmers attach a copyright notice to their work with their name and the date of publication. Trade secrets are not considered part of IP law in Hong Kong and fall within the purview of confidentiality agreements rather than legislation.

The downside to using Hong Kong for offshoring your IP is that, despite its favorable tax policies for businesses, income that is derived from a Hong Kong trade, profession or business carried out in Hong Kong is taxable. Registering IP in Hong Kong would qualify under this definition, meaning that all royalties received by a non-resident for the right to a patent, design, trademark, secret process, or copyright material would be subject to the 16.5% tax rate for corporations or 15% for unincorporated businesses. While certainly not terrible, it’s not the best you can find.

Dubai offers patent, trademark, copyright and design rights. Patents are granted for 20 years and utility models for ten. Trademarks must be registered to be protected by Dubai’s IPPD, although well-known marks are protected to a certain extent without registration.

Copyright can also be registered with the IPPD and is generally recommended despite the fact that the copyright is granted upon creation. Design rights are also registered with the IPPD and protection is extended for up to ten years. Trade secrets and other confidential information is protected in Dubai under the general, criminal and labour laws.

Because the United Arab Emirates is a tax-free jurisdiction, the only fees you will pay for your IP rights will be those required to record a license or register your creation.

Hungary is a rising star among IP-holding locations. The country offers IP rights for patents, trademarks, industrial property, trade secrets, software, and other assets that function as patents such as designs, plant variety types, medicinal products, etc.

The tax rate can be as low as 5% and as high as 9.5% thanks to a 50% deduction from taxable income. Any IP acquired or developed by a Hungarian entity after January 2012 can be sold tax-free as long as the acquisition of the IP is reported to Hungarian tax authorities within 60 days of the sale.

The Cayman Islands recently underwent positive changes to its laws concern intellectual property rights. As of August 1, 2017, the Cayman Islands has a stand-alone trade mark registry system independent of the UK and EU systems. Previously, anyone wishing to register a mark in the Cayman Islands had to register first in the UK and then request an extension.

This is still the case for patents, copyright and design rights, but the jurisdiction has begun the process to create in IP regime independent of the UK, which can only mean good things for the autonomy of the Cayman Islands.

This is especially encouraging considering that there is no corporation, income, or withholding tax levied in the Cayman Islands. Still, in order to claim the greatest tax benefits, you will need to be able to show that there is mind, management and control, and substance for your business located in the Cayman Islands.

Unlike the previous setup in the Cayman Islands that required a request for an extension of a UK registration of IP, the Bermuda Patent Act allows for the automatic registration of a patent granted in the UK. The patent grants the owner exclusive rights to the use of the invention for a 16 year period and can be renewed for seven-year terms. And, unlike Hong Kong where the process can take up to five years, the registration process for patents in Bermuda takes just three months.

Cyprus has one of the most attractive IP tax regimes in Europe. As an EU member state, Cyprus is a signatory of all major IP treaties and protocols. It also offers a low corporate tax rate of 12.5%, meaning that, with the 80% tax exemption on royalties for IP holding companies, the effective tax rate is a mere 2%. Payments can also be received absent withholding taxes.

While they do not offer comprehensive plans for IP rights, there are several countries that you may want to take into consideration for further IP tax planning.

The Netherlands offers a 5% rate for self-developed patents. This lower rate can also apply to non-patent related activity if an R&D certificate has been granted. Coverage in the Netherlands is not as extensive as in other countries; both copyright and trademarks are not included in the country’s IP tax laws. Nevertheless, the absence of royalty withholding tax makes the Netherlands an attractive intermediate jurisdiction.

Belgium began its IP system in 2008 and modeled the plan after both Luxembourg and the Netherlands. It offers an 80% deduction rate for income derived from patents licensed in the country, making the effective tax rate in Belgium is 6.8%. However, like the Netherlands, the IP rights offered in Belgium are limited. Unlike the Netherlands, Belgium applies a royalty withholding tax of 15%.

In 2009, the United Kingdom announced that they would join the IP bandwagon as well. However, they too limited their IP regime to patents, excluding copyright on computer software and trademarks. While not as low as the 2% offered in Cyprus, compared to the UK’s 24% corporate tax, the 10% rate for intellectual property is decent.

Finally, while Denmark does not have an IP regime, it could provide an interesting solution for copyright structures. Denmark’s domestic definition of royalties does not include copyright, meaning that the royalty withholding tax is not applicable to royalties paid on copyright in Denmark. This makes Denmark an attractive intermediate jurisdiction for copyright royalties.

Wherever you choose to register, the key is to start early. Structuring your IP rights is an increasingly important cog in a successful international tax plan. The number of countries getting into the game increases every day. More competition is usually a good thing for you and me, giving us more options to work with. While it does require greater due diligence, it is an important step that should not be skipped.

Determining your IP asset structure early on in the development process will ensure that you will have greater flexibility down the road to transfer assets and enjoy the profits from your creations.